Norms & Behavior Change, Part 2: Leveraging Norms in Your Messaging

12/9/23 / Jane Klinger

In Part 1, we discussed the power of social norms—when and why people follow along with the behavior and expectations of others. How, then, do we leverage these ideas to craft effective appeals and promote public good?

Photo by Melanie Deziel on Unsplash

Anatomy of a Normative Appeal

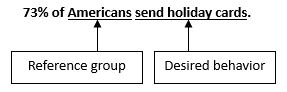

Let’s quickly review to establish a common language. The audience is whoever you intend to reach with your normative appeal. We’ll also talk about the reference group and the desired behavior. As an example, a card company might share that:

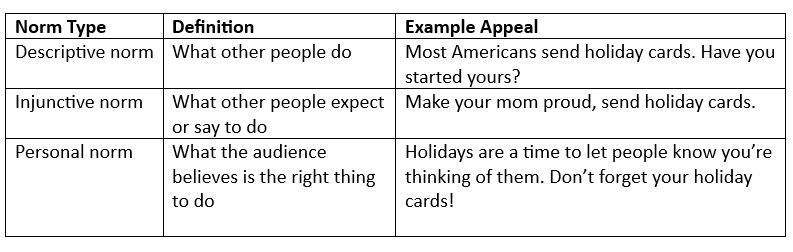

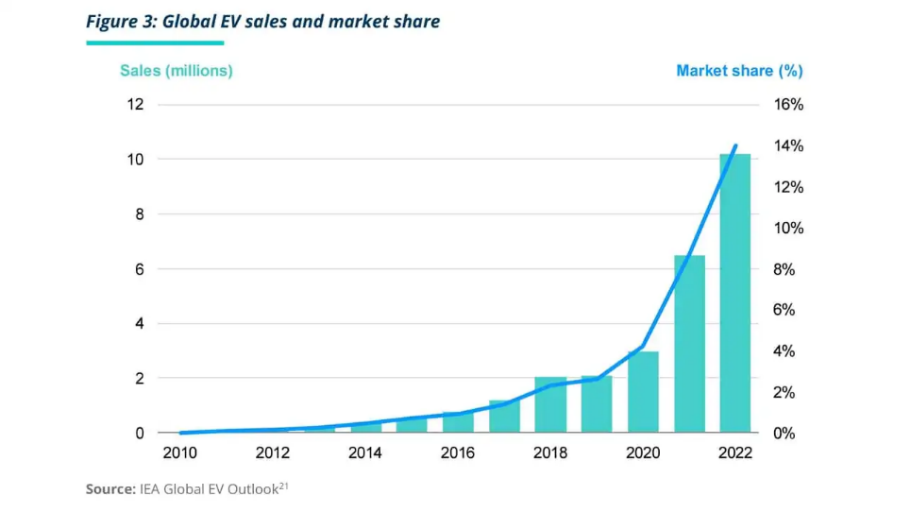

When people say “norm,” they typically mean a descriptive norm, like the example above—information about how other people behave—but you can appeal to other types of norms too, sometimes to greater effect.

What normative information do you want to center in your appeal? What should you consider when choosing the reference group or the type of norm you appeal to? Let’s take a closer look.

Crafting Your Appeal

First, what challenges and data do you have to work with?

In some cases, you may have flexibility in choosing the behavior you want to promote. To choose a behavior for a normative appeal, two practical considerations are: 1) Is the behavior common? and 2) Are people likely to have strong habits and beliefs around the behavior? As we saw in Part 1, social norms have less power to promote change when competing with strong existing habits and beliefs.

Often, however, you may already have a desired behavior in mind. Certainly, it helps if the desired behavior is a common and uncontested one, but if not, the hope for an effective normative appeal isn’t lost. There’s nothing magical about “most” people doing something—it’s really anything that points to people like you do this and think it’s a good idea, i.e., social proof. If the behavior isn’t especially common in the general population, is it more common in an important subgroup? Is it a growing trend? Is it more than people expect? Any of these could be persuasive information. Let’s say, for example, you want people to consider going electric for their next vehicle purchase. Electric vehicle sales are still a small fraction of the market share. Yet, the increasing trend of sales may be persuasive normative information: People are starting to purchase EVs more and more.

[source: https://insideevs.com/news/687300/falling-battery-prices-to-spur-ev-demand/]

Another option is to appeal to a different type of norm. Perhaps most people don’t do it (it’s not the descriptive norm), but you could make the argument that a cool or trusted authority recommends the behavior (appealing to an injunctive norm) or simply that it’s the right thing to do (appealing to a personal norm). Injunctive and personal norms are also likely to shine in cases where it’s more difficult to get traction—say, if your audience is starting from a place of skepticism about the behavior. The descriptive norm appeal, “people are doing it,” can be surprisingly effective on its own, but it’s likely to be a weaker nudge in cases like this. If your audience has the capacity and motivation to really think through your message (that’s a big if), a strong argument about the right thing to do or what a trusted person says to do is likely to be more persuasive.

What reference groups will resonate most with your audience?

A big make-or-break factor for the efficacy of a campaign is the group or authority you reference—”So the behavior is ‘common’ or ‘right’… huh? Common for who? Says who?” When choosing a reference group, consider these two questions: 1) Does your audience trust them? and 2) Does your audience like or seek approval from them? This goes back to the main reasons people conform, as we learned in Part 1—to do the right thing (informational influence) and to fit in (social influence).

Knowing that people do the desired behavior all over the world can be a very powerful appeal, but don’t underestimate the power that a more targeted reference group can have. Depending on the behavior, people often have higher trust for others who are similar in some way—say, people who live in the same town or share the same cultural background or political affiliation. People also tend to identify and seek approval from groups in which they’re closely integrated. For a conservative audience, for example, it’s likely more impactful to know that other conservatives recycle vs. the general population. Political affiliation is a strong identity, but even trivial similarities can build liking and trust.

Lastly, it’s also worth considering your authority in conveying normative information. Let’s say you make the normative appeal: “More and more Coloradans are going electric.” According to who? Did you conduct or vet the research? I was surprised at the statistic above, for example—that 73% of Americans sent holiday cards in the most recent data (2021)—but learning that the research was conducted by AmericanGreetings.com does make you wonder! Providing reputable sources without conflicting interests is the best way of bolstering trust. Subtle cues, like an official company logo, can help too. You can also convey the reference group in different ways—explicitly or more subtly, e.g., with a model depicted doing the desired behavior and a careful eye to the model’s appearance.

In summary, following from what we learned in Part 1, a normative appeal is more likely to work when:

- The audience doesn’t already have well-formed beliefs or well-worn grooves of behavior.

- The norm type suits the audience and situation.

- The audience trusts you and the reference group—and respects you as an authority.

- The audience identifies with the reference group.

Our final post, Norms & Behavior Change, Part 3: Case Studies, takes a closer look at specific examples of public messaging.