The Wages of Engineering Grads

1/21/15 / Kevin Raines

In two previous blogs (Once an Engineer, Always an Engineer? & The Career Evolution of Engineers),

we examined the long-term occupational patterns of people with engineering degrees, by looking at a sample of 1,250 Colorado residents who hold bachelor’s degrees in engineering.

We saw that many people with engineering degrees do not actually become working engineers. In fact, only about half of engineering degree holders are working in technical fields. So the question arises of whether they sacrifice income to do so, or whether they thrive in other occupations.

We conducted an analysis of pay by occupation and degree type (engineer/non-engineer) to explore this issue. In order to develop as close a comparison as possible, we considered only full-time workers (40+ hours per week) in Colorado who reported making more than minimum wage and who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. This eliminates workers in family businesses, entrepreneurial startups, retired people, and workers who choose to work less than full-time. By limiting the analysis to people who hold college degrees, we also provide a comparison of the value of an engineering degree against other degrees in fields other than engineering.

So we can now address the question of “Is an engineering degree portable if a graduate decides not to pursue engineering as an occupation?”

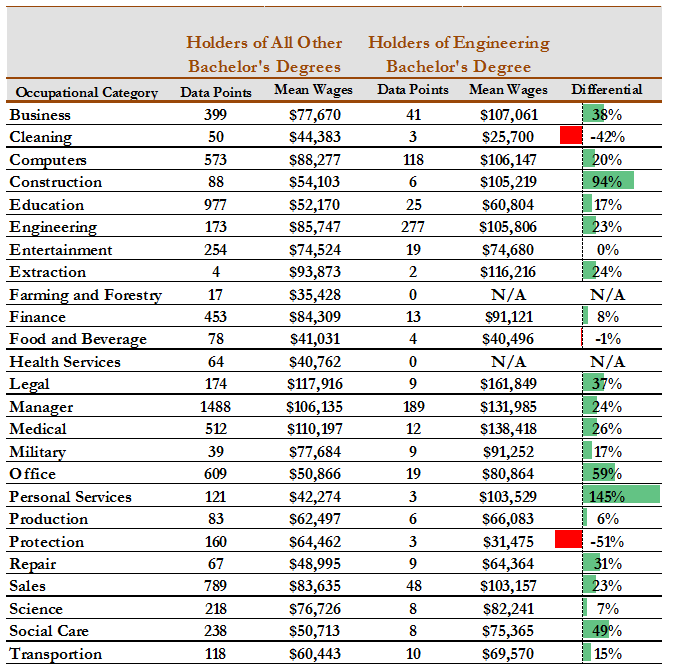

The following exhibit shows the mean wage of full-time degreed workers in different major occupational categories. Partway down the table, we see that full-time engineering grads working in engineering occupations have a mean income of slightly less than $106,000 per year. We can draw several other conclusions by comparing this figure to other occupations.

While the available data are very limited in numbers in many cases, we can still see patterns.

- First, engineering grads make similar incomes or even higher in several other fields. Engineers who have gone into business, computers, construction, legal fields, management, medical fields, personal services, and sales have managed to secure similar incomes as they would have in engineering. So in some cases there’s no financial sacrifice to leave engineering for another career.

- Second, when engineering grads go into lower-paying fields, they tend to out-earn their coworkers who hold other types of degrees. This is particularly intriguing, because one would theorize that engineers are not receiving specialized training for those fields, while at least some other degree holders are.

- Third, there are some fields where engineering degrees are not portable, but for the most part these are field where college degrees do not add as much value. Cleaning, protection (security), and food service are the three fields where the engineering graduates actually earned less than their other degreed peers.

- Fourth, we see a large body of people who list their professions as engineers, and yet do not hold engineering degrees (or at least not bachelor’s degrees). These people have notably lower wages than those who hold engineering degrees. Given the specificity of the field, it’s possible that this is an indicator of other occupations co-opting the term “engineer” when they aren’t engineers in a technical sense.

So what conclusions can we draw from this? For people like myself who have left engineering careers, and for others who are considering leaving the field, the results are heartening. We can conclude that engineering degrees are highly portable to other fields. In many fields, an engineering grad can completely replace his or her engineering income, leveraging those skills in new arenas. And even if an engineering grad decides to pursue a field that pays less than engineering does, the degree itself is still a good thing, rewarding them with higher earnings compared to our peers in the new profession.

Overall, it appears that you can’t really go wrong with an engineering degree, so I’ll continue to display my diploma proudly.